This flimsy 14-page souvenir booklet was published in 1937 to mark the occasion of Grey Owl's second tour of the United Kingdom. Its discovery was the result of a long, hard search on my part, and was snatched from the hands of another, equally anxious bidder on Ebay at the last second or two of its auctioning. Doubtless, I paid well over the odds for it, but with reasonable justification. Subsequent searches, with no result, must attest to its rarity, despite the fact that they were probably printed in their hundreds, if not thousands. Grey Owl's published books, however, are still relatively easy to obtain, and with several subsequent biographies on the market, it is clear that interest in this rather charismatic early pioneer of nature conservation and education remains strong.

The reason why I wanted it so badly was because, as a child, I grew up with another copy that had once belonged to my mother. It was kept in the bottom drawer of my parents' heavy dark-wood sideboard, along with a button box and a souvenir brochure for the 1951 Festival of Britain. The booklet became something of a talisman for me, and I grew up with a keen interest in anything and everything to do with Red Indians (the term 'Native American' not being a concept we fully understood the meaning of back then). The black and white Westerns of my fifties childhood never seemed to give the poor Indians anything remotely like an even break, and no one, but no one seemed to speak up for them. I naturally gravitated toward their teepees, their eagle feathers and their buckskins, and images from the National Geographic, that staple of the dentist's waiting room of the day, also fuelled my passion, somehow painting a far more reasoned existence for the people of the Plains than any John Ford movie could. It would be fair to say that, until the Beatles were invented, my pin-ups consisted largely of those wondrous Edward Curtis photographs, or else beautifully rendered watercolour images of 'Indian' encampments by George Caitlin, and my companions those Indian brave and squaw dolls that were a staple of the Woolworth's toy departments of my childhood. I lost count of how many I had; sufficient certainly for a tribe. Their eyes closed when you laid them to sleep, and the squaw had a tiny papoose strapped to her chamois-covered back. Of course, they were all identical, but this was a detail I overlooked by extra embellishments to their headgear from the family budgie and, if I recall, providing them with a teepee made from old dusters with sweet-pea stakes for tent poles. An over-zealous Golden Retriever puppy probably saw many of them off to the Great Beyond (they were, as I recall, relatively fragile; manufactured, one would imagine, in Japan or China and from that brittle kind of plastic) but as long as Woolworths continued to sell them, I would badger my poor aunt and mother for replacements.

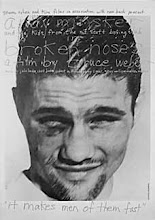

The copy of the booklet that I grew up with was probably issued in 1935, two years before the one I hold in my hand. Not recognising it then, as I do now, that the portrait of Grey Owl that comprises the front image was painted by Sir John Lavery, I loved it simply for the powerful presence of its sitter, gazing out towards the viewer with heavily fringed buckskin sleeves folded across his chest and eagle feathers in his coal-black hair. Of interest (especially when I recall how long I must have gazed at the booklet's cover as a child), is the way in which I hadn't remembered it completely as it appeared when I saw it again, all those years later. However, when I opened the envelope that contained the booklet, it bought back a flood of recollection; about the place where I grew up, my obsession with all things Indian, but most of all, it bought a sense of sadness, as it was the one thing amidst the debris and confusion that my father had failed to find for me when my parent's house had to be cleared quickly. Of all the clutter that could cheerfully have been foregone, this, the flimsiest of ephemeral items, had vanished forever, and with it, perhaps for good and all, my childhood. Amazingly, the ticket for Grey Owl's appearance at Shire Hall that my recently-discovered copy included, is in excellent condition, and was an unexpected bonus.

What my mother's copy contained, however, was a black and white photograph of herself, aged I would guess, around fourteen (given that Grey Owl's first UK tour was in 1935), pictured with Grey Owl himself. Subsequently of course, I have questioned my mother about the time that he visited the school she attended in Tottenham. She could recall the booklet and even the visit itself, but not the existence of the photograph. I can only imagine that it was a bold step on the part of the school authorities to have a photographer present for the occasion which must have been a rather magical occurance, given the everyday-nature of a mid-thirties childhood. I think that it was the loss of this photograph that affected me the most, and whilst I am very fortunate to have found another copy, it makes the foregoing of the other (and the thing it contained) the more poignant. What is perhaps interesting, but merely in terms of spooky synchronicity, is that the date on the ticket for Grey Owl's appearance at Shire Hall- December 11th- is my mother's birthday.

We now know much more about the life and works of Grey Owl. History has rather rewritten the story of the pioneer Canadian naturalist, whose mission it was to tour the world in order to bring a greater understanding of the animal kingdom and its workings. He was born Archibald Stansfield Belaney, in 1888- not of Native American parentage, but in Hastings, East Sussex, and into a family of farmers. His father drank away what fortune there was, and some sources suggest that Belaney's mother was little more than a child herself when she became pregnant with him. Raised by his grandmother and two maiden aunts, he expressed a keen interest in nature and in native cultures from an early age. He attended Hastings Grammar School until he was sixteen, beginning his working life in the local timber-yard, but, according to an early biographer Lovat Dickenson in 'Wilderness Man' (1974), was dismissed for dropping a bomb down his employer's chimney. Belaney emigrated to Canada in 1906 in order, it was said, to study agriculture. After a spell in Toronto, he moved to Temagami, Northern Ontario and adopted a native American identity and the name for which he would become best-known. Marrying a member of the Anishinaabe tribe, Angele Egwuna, he then worked as a fur-trapper, a wilderness guide and a forest ranger. He fabricated his past, stating that he had been the child of a Scottish father and an Apache mother, and had emigrated from the U.S. in order to join the Ojibwa people. In World War One, Grey Owl joined the 13th Montreal Battalion of the Black Watch. The unit was shipped to France, where he served as a sniper. His associates always regarded him as having come from Native American stock. He was wounded twice in 1916, and the latter incident resulted in the onset of gangrene, whereafter he was shipped to England in order to receive proper treatment for his injuries. Having been moved from one Infirmary to another whilst doctors attempted to heal him, he was finally shipped home to Canada in 1917 with an honourable discharge from the army and a disability pension. It was during his time in England that he re-met and subsequently married his childhood friend Constance Holmes, but the marriage was not to last. In 1925, he met Gertrude Bernard, a native of the Iroquois tribe, who encouraged him to stop his fur-trapping-which. on his return to Canada, he had resumed- and to publish his writings about wilderness issues and the lives of animals. As a result, he attracted the attention of the Dominion Parks Service, and he began to work for them as a naturalist . In 1928, the Parks Service made him the subject of a documentary film entitled 'Beaver People', which featured Grey Owl and his wife playing with their pets.

In all aspects of his books and subsequent documentary films, he actively promoted the concept of environmentalism and nature conservation. His two extensive tours of the United Kingdom -which included a return to his native Hastings- he wore the familiar Ojibwa costume to promote his books and lectures. Still alive, his aunts recognised the prodigal, but remained silent about his origins and upbringing until the end of 1937, when they effectively aided and abbetted his unmasking to the media. On the latter tour, he met the young princesses Elizabeth and Margaret at Buckingham Palace. Exhausted from his journeys up and down the UK, he returned to Canada, and to his cabin at Ajawaan Lake, dying the following year of pneumonia on April 13th. He is buried in the grounds of his lakeside retreat. After his death, questions began to arise as to his true identity, and a local newspaper 'The North Bay Nugget' ran an expose. The story was soon taken up by national, and then international organisations, including the London 'Times'. Lovat Dickenson, his publisher, attempted to maintain Grey Owl's chosen identity, but was forced to admit that his friend had lied to him also. 'Grey Owl' was indeed a fabrication; an invented Indian like so many others. Consequences of the revelations were dramatic; an immediate cessation of his book publications, and in some instances, with extant copies being withdrawn from sale. As a result, donations for conservation causes that Grey Owl had been so anxious to promote were very badly affected.

Richard Attenborough (who recalled meeting Grey Owl as a fifteen-year old boy) released a film of his life in 1999. It received mixed reviews and was not shown in the U.S. On the 100th anniversary of his birth, a Canadian Red Maple tree was planted in the grounds of Hastings Grammar School, and in 1997, the mayor of Hastings unveiled a plaque dedicated to Grey Owl on the house in which he was born. In the town's museum is a full-sized replica of his Canadian lakeside dwelling, with a display of memorabilia (including, I believe, a copy of this brochure) and a selection of his published works.