First published in 1952, Flannery O'Connor's blackly allegorical novel 'Wise Blood' is considered to be a masterpiece of the Southern Gothic genre. The grotesquely comic reality of its themes, conflated with elements of the truly absurd, and with over-arching tragedy of the central character at its dark heart were bought to the screen in 1979 by the veteran director John Huston, after having been sent a copy of O'Connor's novel by the son of her literary executor Robert Fitzgerald. Then his mid-seventies, and with a string of illustrious movies behind him, Huston (who, after 'Wise Blood', was to make two further feature films adapted from major novels; Malcolm Lowry's 'Under the Volcano' in 1984 and - in 1987, 'The Dead'- the final, magnificent story of love and loss in Joyce's 'The Dubliners') must have considered the task of bringing O'Connor's novel to the screen a daunting prospect, but the result is a haunting, cinematic triumph that once witnessed, remains forever in the heart and mind of the viewer. Huston had always considered O'Connor to be a major voice in American literature, and his faithful rendering of 'Wise Blood' remains to date, the only major feature film based on her writings.

Shot almost entirely in and around the town of Macon, Georgia, in a period of forty-eight days, Huston employed a scant technical crew that he backed up with assistance from the city's fire and police departments. With a screenplay closely adapted by Fitzgerald that stuck largely to the sequences of events as they unfold in O'Connor's narrative, the novel's themes of false redemption, heartbreak, marginalisation and displacement are closely adhered to, and the plot loses little or nothing of O'Connor's unsettling, fractured narrative. Originally set in the 1950's when, we assume it was period immediately following the Korean war that O'Connor had in mind, Huston chose instead to update the action to the mid-seventies, where presumably it is as a Vietnam vet that Hazel Motes returns to his childhood home, only to find it eerily derelict, with little or no trace of his past to attest to his identity, his relatives dead or missing. Despite his stated hatred of the established church and of preachers in particular, he travels by train to the city of Taulkinham and decides to establish a new order -'The Church of Truth Without Jesus Christ Crucified', which advocates a humanistic reliance on self, rather than on God. Presumably as a result of his experiences in the army, Hazel has reached the conclusion that the only way to escape sin is to be devoid of soul. Immediately on his arrival in the new town, he takes a taxi to an address that he has found in the station washroom, which in truth is the calling-card of one Leonora Watts, a homely, part-time prostitute who, upon his avowed insistence that he is not a man of the cloth, reassuringly tells him ' Mamma don't mind if you ain't a preacher', and promptly provides him with her services. 'I'm obliged', he drawls to the bemused cab driver, who is seemingly at odds to equivocate Hazel's newly-acquired priestly vestments with the profession of the addressee to whose house he has taken him.

The following day, he encounters a street vendor who is selling potato peelers to a crowd that have gathered around him, and also the disillusioned eighteen-year old character of Enoch Emery, whose semi-itinerant status has been bought about by his abandonment at the hands of an uncaring father. With a nothing-job in the local zoo, Enoch is cynical and impatient with his unfortunate simian charges, and seemingly, none of his efforts endear him to Hazel, who is impatient to be rid of the pestering boy. Seeing another lost soul in Hazel Motes, Enoch tells his that he has the gift of 'Wise Blood' inherited from his estranged father-which affords him the ability to 'know things'. The huckster's patter is interrupted by the arrival of a 'blind' preacher. Asa Hawks, who is accompanied by his daughter Sabbath Lily. Motes immediately senses an indefinable charisma in the character of Asa, yet seizes his moment, testily diverting the crowd's attention from the other's ministry with a sermon about his own newly-formed church. Motes is strangely attracted to Sabbath; Asa in turn, is drawn to the interloper. Having ostensibly blinded himself with quicklime, his affliction turns out to be a conceit, but he continues to prey on the sympathies of the multitude, fiscally-assuaged by the faith they stake in his mission. Enoch shows Hazel a shrunken, dessicated corpse that lies in a vitrine in the local museum, but Motes is unimpressed. The weeks intervene, and Hazel's 'Church of Truth' staggers along with himself as both preacher and sole-disciple. He has bought a clapped-out car from a rogue dealer, and convinces himself that it will provide him with shelter and get him form place to place so that he can spread the word of his mission. 'No one with a good car needs to be justified' he tells the feckless dealer, as the vehicle wheeezes and lurches off the lot.

Enter self-confessed Christian evangelist Hoover Shoats. aka Onnie J.Holy (played magnificently in Huston's film by Ned Beatty), who sees a money-making opportunity in Hazel's new religion, and attempts to hijack it for his own ends, hiring a feckless individual whom he picks up on the street, dressing him in Hazel's trademark black suit and wide-brimmed fedora, and sending him out as a stalking horse for the 'new' faith. Later, Motes runs the pretender out of town, sides his car into the ditch, and then runs over him with his own, killing him. Meanwhile, Hazel has sought out the house where Hawks and his daughter are living, and has taken an upstairs room so that he can plague the pair and unmask Asa for the fraudster that he knows him to be. Enoch, having heard Motes' plea for the need of a 'new Jesus' in his ministry, steals the strange, mummified corpse from the museum, convinced that it is the messiah that the newly-converted will crave, once it is in Hazel's possession, taking it to Mote's apartment, where Sabbath is now also living. Furious to discover that Sabbath somehow adopted the creature as a sort of divine progeny, he hurls it out of the window. In a later scene we see Sabbath, who has managed somehow to reclaim the mummy's head, sleeping with it in their communal bed. In absurd counterpoint, a van with loudspeakers is announcing the arrival of 'The Mighty Gonga' to town, a King-Kong like creature who appears before a crowd at a downtown movie theatre. In reality, of course, it is a man in an ape suit, and with whom Enoch becomes obsessed, believing that there is some affinity between his charges at the zoo and this 'wild' creature. In the film, a tracking shot of the van leaving the city limits ends with Enoch climbing into the truck, later to emerge in the gorilla suit, in which he proceeds to terrorise townsfolk at night. Motes decides to leave town and move on, but the town's sherif stops apprehends him on the road, and forces him to get out of the by now decrepit car, which he then proceeds to roll down a hill into a lake, Now, with no possessions, no car and no direction, Hazel returns to the house and proceeds to blind himself with quicklime in the belief that asceticism and suffering will be the key to his new existence. Investing a passionate belief in suffering and pain, he binds his bare torso with barbed wire and walks with shoes full of rocks. Mrs Flood, his lonely, long-suffering landlady (played magnificently in Huston's film by Atlanta-born stage actress Mary Nell Santacroce, whose quietly-powerful performance is a fine counterpoint to Brad Dourif's tortured Motes) sees that now, Hazel is utterly reliant on her for his care, eventually proposing that she marries him in order to keep him with her. Mrs Flood's suggestion that he gets a 'seeing dog' and returns to preaching is met with rebuttal; Hazel tells her that he 'doesn't have the time'. Her preoccupation with his well-being drives him to distraction, and after telling him that she wants him for a husband, he wanders off in the torrential downpour. Huston's clever use of the rain in that scene in the film is a hugely-effective juxtaposition to Mrs Flood's quietly- uttered proposal, and is both haunting and unforgettable. Discovered three days later in a ditch, the policeman deliver the semi-conscious Hazel back to Mrs. Flood's house, where he then dies.

Premiered at the New York Film Festival in 1979, 'Wise Blood' was rapturously received by critics and audience alike. Vincent Canby, film critic for The New York Times; declared in to be 'one of John Huston's most original, most stunning movies. It is so funny, so surprising and so haunting that it is difficult to believe it is not the first film of some enfant terrible instead of the thirty-third feature by a man who is now in his seventies'. Canby opined that the film was 'lyrically mad and absolutely compelling even when we don't fully comprehend it'. Another review concluded that 'it was the best realised religious movie of the decade'.

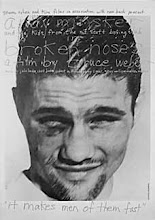

At the heart of Huston's film lies the powerhouse performance of Brad Dourif as Motes. In retrospect, it is difficult to imagine any other actor of his generation in the role. Previously most noteably known to a generation of cinema-goers as Billy Bibbit in Milos Forman's masterly adaptation of Ken Kesey's 'One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest' (1975), Dourif's portrayal of the redemption-seeking outsider is unforgettable from the opening sequence when he becomes the passenger in a passing pickup truck to the moment of his demise. Treading a fine line between huckster and fallen angel, Dourif embodies the role of what O'Connor herself termed Motes' 'malgre lui'- the personage of a king in spite of himself. She states that '[his] integrity lies in his trying with such vigor to get rid of the ragged figure who moves from tree to tree in the back of his mind. For the author, Hazel's integrity lies in his not being able to'.

How do you pick the best suit for you? In order to buy suit choose the best one who have a great offer.

ReplyDeletecanada goose

ReplyDeleteconverse shoes

off white nike

yeezy boost 350

curry 5

lebron 15

adidas superstars

curry 5

nike air max 270

yeezy

Go Here her response discover this blog link investigate this site this hyperlink

ReplyDeletetop article replica dolabuy browse around this website gucci replica bags browse around these guys YSL Dolabuy

ReplyDelete