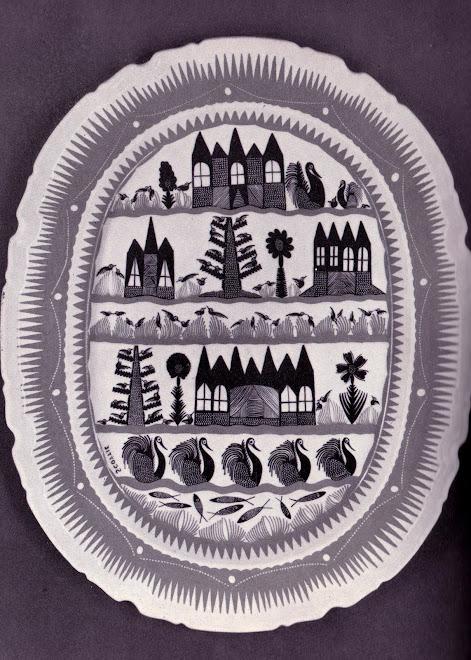

Few examples of iconic packaging have sustained the longevity of the Lyle's Golden Syrup Tin. Against all odds (and probably little resistance) its design has endured without significant alteration for almost three hundred years, save perhaps the bringing of weight and content descriptions into the 21st century (and, for example, on the occasion of the Queen's Golden Jubilee, where the distinctive banner over the lion was appended by an impressive crown and a cheer of suitable lettering to mark the auspicious occasion).

Born in Greenock in 1820, Abram Lyle was, by the 1860s a successful owner of a fleet of ships that brought sugar from the West Indies. In 1881, he sold his shares in the company and with his three sons, opened a new refinery on the Thames at Plaistow adjacent to those of the sugar cube magnate Henry Tate (these two giants of the sugar industry would later merge in 1921, forever lending legendary status to the partnership). Lyle's problem was to effectively turn the bitter, hitherto wasted by-product of the sugar-refining industry into the sweetly viscous syrup for which his name is perhaps best known throughout the world, and it was a research chemist named Charles Eastick to which the task fell. Eastick was an expert in the specific properties of sugar and its refining process, and Lyle wasted no time in employing his services. Almost an overnight sensation, the syrup was initially dispensed from wooden barrels for local consumption and it was in 1885 that the first distinctive green and gold cans with their cryptic Old Testament imagery began to appear on cornershop shelves. 'Out of the Strong Came Forth Sweetness', and the seemingly eternal mystery of the lion which defines the very essence of the tin's design, relates to an episode from the Book of Judges, and to Samson in particular. Judges relates the slaying of a lion by the strongman whilst en route to woo a prospective wife from among his Philistine oppressors. On returning homeward, Samson discovered that a swarm of bees had made a honeycomb within the dead creature's carcass, and he availed himself of its sweet delicacy. Here then, is offered up a riddle with which he confronts his oppressors during the wedding feast that was to follow: 'Out of the eater came forth meat, and out of the strong came forth sweetness'. The image of the dead lion with his emerging swarm of bees has intrigued us down the centuries, and remains perhaps the most tantalising aspect of the product's distinctive packaging, and the element by which the tin is regarded by millions with nostalgic affection. There is also perhaps, a further, slightly tangental dimension to the image of the recumbent beast and his swarm of insects - that which centres around the ancient concept of Bugonia, or 'The Ox-Born Bee'. Bee Wilson, in her groundbreaking study of man's eternal relationship with the honey bee, discusses what is perhaps the oddest of all ancient theories on the origins of how these creatures came into existence and how their species were generated and sustained, namely, that they were somehow spontaneously fashioned from the dead body of an ox. The Latin poet Ovid (43 BC - AD 18) declared that 'Swarms rush from the rotten ox, and one extinguished life produces a thousand'. The notion that a decaying carcass might give birth to living bees is fanciful by any standards, yet bizarrely, this was an accepted explanation for the existence of bees of more than 2,000 years. In part it was a reflection of the yearning of man to control the miraculous creatures and, by extension, thereby to have domain over death itself. The Greeks coined this supposed process of creation Bugonia (literally 'Birth from an Ox') and since both creatures were revered in equal measure, opined that the death of one might give rise to the life of the other. Columella, an agricultural expert writing in the 1st century AD, went so far as to believe that oxen and bees were related. In Rome, the process of apes facere was spoken of; namely, the practice of 'making' bees; as though they might be manufactured at will by human beings. Ovid further writers of the use of a rotten ox to 'recover bees by art', and creating them in this manner meant that mankind could dream of standing in relation to bees as gods did to mankind. The superstition that the life of bees derived from the carcass of dead oxen predates those of the Roman poets however. A version of the belief possibly began in ancient Egypt, where the sacred Apis bull was worshipped for its fertility and its strength, as the bee was for the miraculous, healing properties of its honey, and where belief in the reincarnation of the soul was strong. In ancient Arabia, there was a similar belief-system involving a dead horse. Here, we must return to Samson and the bees, perhaps the best-known variant of the bugonia legend, and to our familiar gold and green tin. Samson's story is allegorical - which is not to say that the ancient attachment to the concept of the Ox-born (or in this case Lion-born) bee was merely fanciful or symbolic. There were many complex tenets to its process, chiefly centred around the method by which the ox must be killed and processed so that the conditions are rendered perfect for the genesis of the swarm to issue forth. Particular emphasis was given to the surrounding conditions of the carcass, with strict geometrical consideration given to the chamber in which the process was carried out. Fragrant thyme played a crucial role, as did the timing of the decaying process - strictly thirty days (after which the chamber was opened for a further eleven, at which point, the miraculous cluster of bees were alleged to swarm 'like summer clouds') and the creature reduced to horns, bone and hair. Belief in the process of bugonia persisted into the Renaissance and beyond, and from ancient poetry to prosaic British methods of animal husbandry. In the 1600's, a Mr. Carew of Anthony, claimed to have successfully manufactured bees from the carcasses of yearling calves, and maintained his swarms not in hives but rather in the decapitated heads of pigs, convinced that the burying of dead cattle at the end of April would produce honey-making bees by Summer. Shakespeare refers to the bee 'leaving her comb in the dead carrion' and Ben Jonson, writing in 'The Alchemist' of 1610 stated; 'Beside, who doth not see, in daily practice, Art can beget bees, hornets, beetles, wasps, out of the carcases and dung of creatures yea, scorpions of an herb, being rightly placed?'

The unique design of the Lyle's Golden Syrup tin is recognised the world over, and by the Guinness Book of World Records as 'Britain's oldest branding'. In our fast-paced and visually changing world, its appeal remains constant thanks to its sense of the eternal.

Saturday, 21 January 2017

Tuesday, 17 January 2017

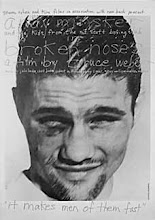

Poster Boys for the Beat Generation

With the

possible exception of ‘Shakespeare and Company’ founded in 1919 by Sylvia Beach

and forever associated with the likes of James Joyce, Ezra Pound and Ernest

Hemingway, City Lights Bookstore, opened in 1953 by poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti

and Peter Martin retains its heritage as the cradle of the Beat Generation

Movement, and one of the few truly great independent bookshops in the United

States. Six decades have passed since the birth of the Beat explosion became

the byword for the burgeoning counterculture in American literature, and

Ferlinghetti’s famous store, located in San Francisco at 261 Columbus Avenue,

remains a destination for book-lovers the world over. Expanded several times

during its 63-year history, City Lights continues to keep the flame of the Beat

Generation alive, with extensive titles by the leading figures of the movement.

Famed for its reprints of important

texts from such luminaries as Ginsberg and Burroughs, there are also sections

on politics, philosophy, music, spirituality and ‘alternative’ lifestyle. With

its famous masthead ‘A Literary Meeting-place since 1953’, City Lights remains

the premier outlet for writers and readers seeking an alternative American

voice. In 1955, Ferlinghetti launched City Lights Publishers with the

now-famous ‘Pocket Poets’ series, and throughout the decades, has published a

wide range of both poetry and prose titles, with over 200 still in print.

Recognised and respected for its commitment to innovation and progressive

ideologies in poetry and fiction, it remains a resistant force in the face of

conservatism and literary censorship, and holds to the tenets of its founders

as an invitation to participate in what they termed ‘the great conversation’

between authors of all ages. Though renowned throughout the literary world, the

store has retained its sense of intimacy, with a liberal dose of anarchic

charm.

Perhaps the

most enduring image of the store remains its poster of Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady,

based on a photograph taken by Caroline Cassady in 1952. Available for sale

since it appeared in the 1950’s, the image was also used for the Penguin

reprint of Kerouac’s ‘On the Road’. First published in 1957, it remains perhaps

Kerouac’s most defining literary achievement – and certainly the work for which

he is most recognised. A classic roman a’ clef, Kerouac employed the key

figures of the Beat movement as characters, including himself in the guise of narrator

Sal Paradise. On publication, the New York Times hailed it as ‘the most

beautifully executed, the clearest and the most important utterance yet made by

the generation Kerouac himself named years ago as ‘beat’ and whose principal

avatar he is’. Continuously in print, ‘On the Road’ was chosen by Time magazine

as one of the greatest works in the English language, whilst Modern Library ranked it 55th

on a shortlist of the best novels of the 20th century.

Caroline

Cassady’s iconic image for the City Lights Bookstore poster was taken in the

early fifties during one of the trio’s many road trips. She met Neal Cassady in

1947 whilst studying theatre arts at the University of Denver. Cassady, a

working class man with literary aspirations, was close friends with budding

writers Kerouac and Ginsberg, and the complexities of their conjoined

relationship was detailed in her memoir ‘On and Off the Road: Twenty years with

Cassady, Kerouac and Ginsberg’, published in 1990. She tolerated Cassady’s

ramblings with Kerouac (and also their on-off sexual relationship) and competed with a series of women

throughout their tempestuous marriage. After ‘On the Road’ was published – in

which he was forever mythologised as Dean Moriarty, Neal served three years in

San Quentin for selling marijuana to an undercover policeman. On his release in

1963, the Cassadys divorced.

Caroline

Cassady’s enduring photograph of Jack and Neal shows two men at the apex of their

beauty, and as avatars of their era, and there is a timelessness to the image which transcends the age of its capture. Lovingly referred to as

‘The Boys’ by Ferlinghetti, the photograph retained its appeal long after the

bloom of the Beat Generation faded, and it remains the essence of both

innocence and experience for those that blazed their own trail in the decades

that followed.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)