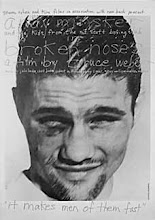

Keith Vaughan (1912-1977) belonged to a

generation of serious painter-printmakers anxious to discover their identity in an artistic universe not only shattered by the events of the Second

World War, but also one which had become largely dominated by European and American

forms of abstraction, where the language of figurative painting was seen to

possess little validation after the reality of recent global events. Chosen to

undertake the vast mural for the Dome of Discovery at the 1951 Festival of

Britain, he was also represented in the landmark exhibition ’60 paintings for

‘51’, Vaughan was regarded in high esteem by both contemporaries and discerning

collectors at this early stage of his career, and possessed of an

uncompromising sexual identity as a gay man (which he shared with Francis Bacon

and John Minton), Vaughan’s figurative work is imbued with a potent male

presence which remains as powerful and uncompromising to the contemporary

onlooker as it did to the awakening audience of the forties and fifties.

Reaching his professional peak with a major retrospective at the Whitechapel

Art Gallery in 1962, Vaughan’s work mirrored the sudden shift of artistic

emphasis that had been dominated by major European and American centres of art,

and ushered in the Pop Art generation with which the art world of Britain in

the sixties is most strongly associated. Despite a career eclipsed by

contemporaries such as Bacon and Freud, Vaughan maintained a powerful

creative output which was to last until his death in 1977.

A timely reassessment of

Vaughan’s life and work has recently been published to accompany an exhibition based on major archive holdings of Vaughan's work at the Aberystwyth University School of Art Museum, and chiefly brings together his overriding preoccupations;

the figure and the landscape. Three scholarly essays – on drawing and book

illustration by Colin Cruise and on Vaughan’s photography by Simon Pierse, the

text also includes a masterly and important re-appraisal of Vaughan as a

printmaker by Robert Mayrick and Harry Hauser. Now much sought-after by

collectors of the post-war artistic era, Vaughan as print-maker has perhaps

failed to attract the scholarly attention this branch of his work justly

deserves. Mayrick and Hauser examine Vaughan’s

printed imagery of the 1950s, beginning with the iconic ‘Festival Dancers’ of

1951. They discuss Vaughan’s lithographic landscapes chiefly populated by

lithe male figures in the act of labour and repose. Recalling in his journal of

1940 ‘naked bodies browning in the sun and salt’, his printed images of the

period reflect a sensual world imbued not only with hard work but also with forbidden

sensuality; Vaughan's private preoccupations made uncompromisingly public.

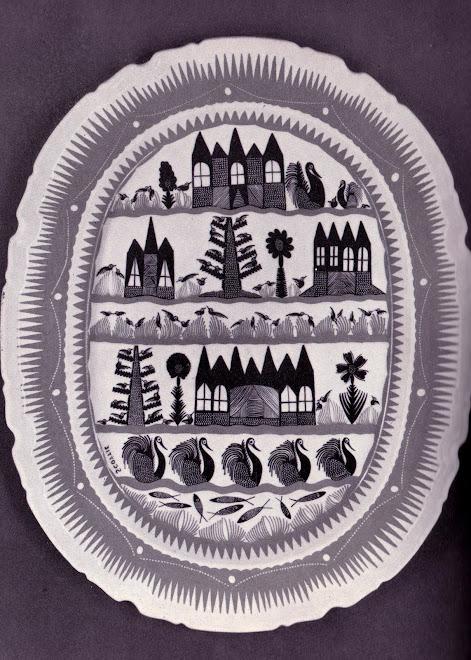

The authors also touch upon Vaughan’s early linocuts, made during his public

school days, which were, by his own insistence, of 'little artistic concern' to the artist himself. Indeed, it was only in 1963, when invited by the Refern

Gallery to edition some prints that had lain undiscovered for over a decade

that a re-interest in the print medium was awakened in him. Whilst these early

linocuts would suggest the influence of Edward Gordon Craig, whose images

distilled the human figure to its very essence, Vaughan’s exposure to

developments in colour auto-lithography in the late 1930’s and throughout the

forties, advocated by contemporaries such as John Piper (and by commissions

from such as Frank Pick at London Transport and Jack Beddington at Shell-Mex,

who actively commissioned artists of Vaughan’s generation to explore the print

medium, commissioning unsigned, open-edition prints for distribution among

public institutions) proved to be the creative fulcrum for what was to follow.

Continuing to largely focus on male figures in landscapes, all of Vaughan’s

extant lithographs were made over a relatively short period. The lithographic

medium appealed greatly to a generation of British artists such as Vaughan and

his contemporaries as the technique was relatively new and –most crucially-

unburdened by the long tradition of other print disciplines such as the

wood-block and the etching plate. Finely crafted etchings and woodcuts that had

been so popular during the inter-war years now seemed staid and conventional by

comparison to a generation in pursuit of the new. Lithography also possessed

the appeal of immediacy, somehow in direct, gestural alliance to the very act

of painting itself. Resolving to shake off his former Neo-Romantic associations,

Vaughan now forged a new direction in both painting and printmaking, and the

latter proved to be the most effective medium for him to make the transition

from his drawings and previous works on paper, preparing him for a decade of

ravishing lithographic imagery.